Hello again!

I hope you have all been able to spend these last few days safely with loved ones. Weather in the PNW has been pretty aggressive!

In this post I will display my rationale. To graduate my college, one must write a ~8 page paper that bounds their studies (and self-named degree). This isn’t an argumentative essay, more so a laying out of topics that will be discussed in a multiple-hour-long ‘colloquium’ (read: discussion) with their primary faculty advisor and another professor. That is why my rationale moves rather quickly and in broad strokes. At the end you will see my ‘List of Works,’ that were core to my studies. (I added five more than the limit allowed, and I wish I could’ve added more about design and aesthetics!) It is divided into certain categories as required by the school. That’s most of the introduction it needs, if you all enjoy this I may post some of my other favorite research papers that I’ve written these last few years.

One of the biggest takeaways I hope readers get out of my rationale is that for too long localized knowledge (at both small and large scales) is disregarded. In the context of technology and society, this has had adverse effects that are hard to spot at face value. A healthy pessimism paired with a focus on the local is not only of value, but ethical. The images have been added after the fact in this post for context and readability. My rationale…

Proposing a New Ethics for ‘Human-Computer Interaction’

I am interested in creating good technologies (especially digital ones), how these technologies impact the people that use them, and how they come to be proliferated through societies. I believe this is an important topic to explore because of digital technology’s increasingly important role in our lives, and because existing systems that produce digital technologies have their roots in problematic age-old theories and debates relating to economics and property. I believe that these current systems of digital technology production, reliant upon notions and economic paradigms from Classical Greece that then develop through the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution, are not ideal. In this paper, I will propose new ways to understand ‘human-computer interaction.’ Because of technology’s broad implications and relations to other social structures, I believe a new ethics of human-computer interaction is necessary.

Before I continue further, it is important to discuss what I mean by ‘human-computer interaction’ (HCI) further. Currently, much of academia and the technology community defines HCI as digital interface design, and occasionally physical product design, coupled with psychology. I believe a more holistic definition is necessary, one that certainly goes beyond visual- and physical-computing and psychology. I will reference the concept of the metaverse to make my point. With computing’s encroachment on the physical body and the ubiquity of AIs, philosophies of metaphysics and ethics are needed to discuss the value of building the metaverse. Applying critical faculties is a useful tool to understand the implications of the metaverse, given that it is attempting to add another layer to people’s social interaction. Building these worlds, platforms, and physical interfaces costs a lot of money; thus, understanding financial systems that lead to certain technologies being developed over others is another hugely important piece of the process. What will the effects of the physical aspects of the metaverse’s computing be on the planet, especially in terms sustainability and ecology? As technologies grow more complex, they begin to impact more and more domains. Because of this, the holistic field of human-computer interaction has wide-ranging implications for many academic disciplines, economies, and communities.

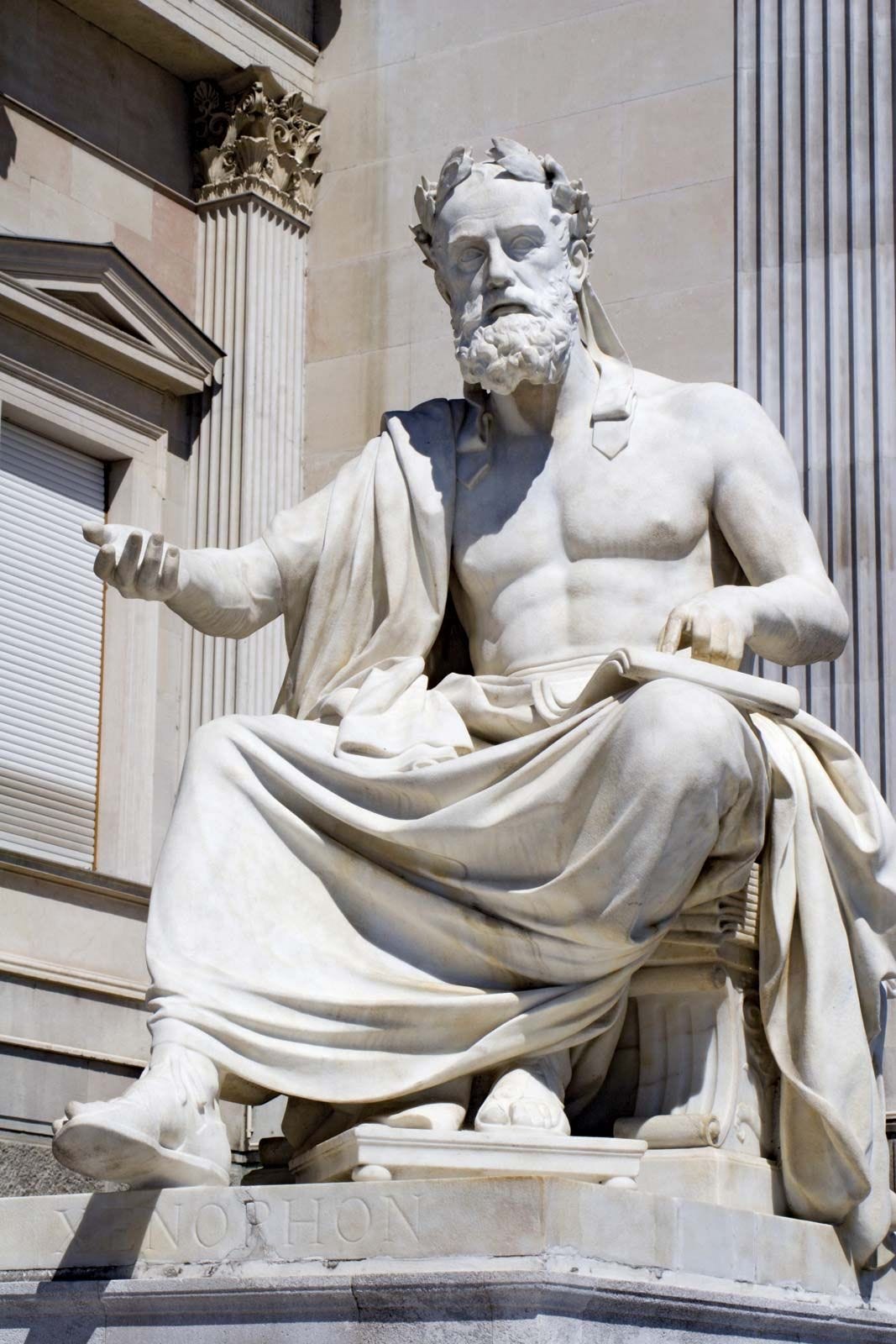

Using the etymology of technology and economics, we can already see threads to old discussions beginning to appear. The world technology comes from two Greek words: techné and logos. Techné means art, skill, craft, or the way, manner, or means by which a thing is gained. Logia means systematic understanding of a concept. Economics comes from the Greek words oikos and nomos. The oikos is the Greek family, household, or estate, while nomos generally means law. Much of traditional Western economic theory is rooted in Classical Greek ideas; many consider Xenophon’s Oeconomicus to be one of the first texts on the concept of Western economics. His ideas have threaded through history since, to today. Referencing Xenophon’s Oeconomicus and Ways and Means from my Risky Business: Law, Economics, and Society in the Ancient world IDSEM, the Oeconomicus in particular sheds light on the ancient antecedents of many contemporary economic notions.

First, we should point out that the classical understanding of economics pertains to the household or oikos. Xenophon argued that managing an estate (one of the primary drivers of Classical Greek economies) well should include effective slave and technology management with the intent of gaining even more wealth. On the second page of Oeconomicus, Socrates asks Critobulus about his ethics of wealth, “Therefore, it seems you consider what is beneficial as wealth and what is harmful as not wealth.” Critobulus responds with a single word: “Exactly” (Xenophon, Oeconomicus. 1.9-1.10). So, wealth originally had a positive teleology that is the antithesis of harm. (Ironic given the Church of Shareholder Value today.) Critobulus continues to introduce economic concepts like ‘surplus,’ discusses the difficulties that measurement and operationalization entail, and the importance of optimizing functions (such as taking care of the home compared to the field). Xenophon highlights how his wife organizes parts of their estate, and how Phoenician merchants meticulously organize their ships (Xenophon, Oeconomicus, 8.11). It is also worth noting that another part of this optimization was separating work based on which gender was best qualified for a particular task by the Gods. According to Xenophon, the easiest and most noble way to accomplish the accumulation of more wealth was by coercing one’s slaves to work more efficiently and according to the outlined order. Discussed in detail is the relationship that one who manages an estate well should have with their slaves. He argued a citizen should act as a moral bastion for his slaves and appointed slave-managers who perform the labor, encouraging them with rewards for good behavior instead of punishments for mistakes (Xenophon, Oeconomicus. 11.11). Xenophons’s project can be taken to be about explaining the advantages of bringing some order to a very chaotic Classical Greek world. However, that does not provide an adequate reason as to why our current systems of technical production still follow in these fundamentally racist and gendered notions.

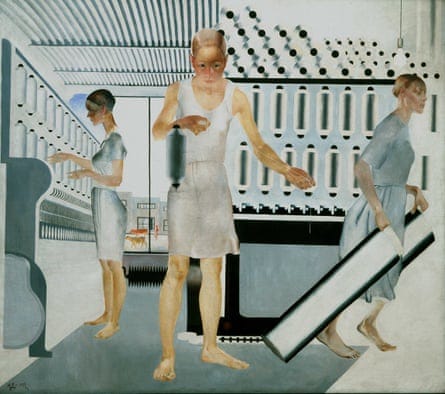

These economic notions were altered during The Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution. Techné was also updated by the Germans to technik, which included notions of mechanization and order. As Scott describes in Seeing Like a State, multiple states began experimenting with top-down technical forestry. In an attempt at bringing more order to chaotic and Romantic nature, new states like Germany began clearing and replanting forests in neatly ordered rows with new species of fast growing trees. Scott describes this approach further: “I believe that many of the most tragic episodes of state development in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries originate in a particularly pernicious combination of three elements. The first is the aspiration to the administrative ordering of nature and society, an aspiration that we have already seen at work in scientific forestry, but one raised to a far more comprehensive and ambitious level. “High modernism” seems an appropriate term for this aspiration” (Scott 88). The results of the high-modernist German forests were an ecological disaster, especially after the first few generations. The multi-natured ecology of a forest was ignored, resulting in a dead forest after only a decade. Also ignored was the deep understanding local forest communities had about their land, and the craft involved in maintaining it. I believe this lack of a ‘bigger-picture’ through over-quantification is also generally the case with human-computer interaction today.

Second, in addition to labor management and motivation, measurement was an important and nebulous notion in the ancient world. This becomes key for how technology is deployed in the contemporary world as well. Tech companies also often determine the success of a product on a handful of ‘North Star’ metrics that often do not capture the full picture. In Algorithms of Oppression, Safiya Noble discusses the biases associated with the tech that we routinely use. Centering the success of an AI driven feed on ‘North Star’ metrics like ‘virality’ and ‘time spent on platform’ ignores how the feed accomplishes these goals. In the case of many AI driven feeds today, this happens by serving users racist, politically divisive, or generally harmful content. Noble summarizes why this is important: “The insights about sexist or racist biases that I convey here are important because information organizations, from libraries to schools and universities to governmental agencies, are increasingly reliant on or being displaced by a variety of web- based ‘tools’ as if there are no political, social, or economic consequences of doing so” (Noble 9). Trusted information systems are being altered—in almost a McLuhan-esque way—by digital tools that are increasingly turning into social actors. Fogg covers this in detail, analyzing how computers and persuasion combine into being a phenomenon termed captology. Fogg, and especially Noble, have studied the ethics behind technology’s impact on society, one of the largest being the design of the teams that build the algorithms.

Dealing with measurement has always been a theme of technical production because of creation’s multiple moving parts that need to be managed. This is especially true in the case of software production, resulting in the adoption of a particular system of production, used by both corporations and startups, called ‘Agile.’ In Agile and the Long Crisis of Software, Posner discusses the motives behind the vast adoption of Agile frameworks in software production and their consequences. Agile has variations, but one of the most popular is the ‘waterfall method.’ In this system, tasks trickle down the corporate ladder, being divided into increasingly smaller jobs- to-be-done on the way down. Software production is difficult to quantify by nature; Agile was popularized in an effort to reign in “software’s most troublesome tendencies—its habit of sprawling beyond timelines and measurable goals” (Posner). Agile is supposed to work against these tendencies. Well-known computer scientist Tony Hoare said that an Agile-inspired computer science education at Oxford would “‘transform the arcane and error-prone craft of computer programming to meet the highest standards of the engineering profession’” (Posner). Agile is now the default framework of digital product production, listed proudly by hiring firms on job listings as a reason to join their firm.

Agile works better than previous systems at organizing programming into distinct timelines, but the nuance around how it impacts the product being built needs to be discussed. Today’s software is largely built through work design whereby “the coder of Agile’s imagination is committed, above all, to the project” (Posner). Regardless of the quality of the software or broader implications, software engineers must work to progress the project expeditiously to maintain team velocity (another internal North Star metric). Because of how development has become dominated by the Agile framework, software engineers often do not understand how what they are building plugs into the broader product, or what purpose it is supposed to serve. This makes issues like racism (referencing Noble) and sexism (referencing both Noble and Zuboff), potentially more prevalent. Agile makes it difficult for ethically dubious products to be built without engineers realizing, especially when products are as opaque as AI.

Third, financial pressures that produce these technologies are also direct results of old financial and economic specters. The majority of new technology is developed in the private sector, particularly vulnerable to the phenomenon of financialization. I am defining financialization as Epstein does: “financialization means the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies.” Given the rise of venture capital (VC), they play a significant role in both domestic and international economies. More specifically, huge amounts of technology innovation is now primarily funded through venture capital. Driven by familiar economic ideals around production and property, VCs have attempted to quantify and standardize what makes a successful ‘unicorn’ just as more traditional investors would. Tom Nicholas chronicles the origins of VC in his book VC: An American History, linking the industry to broader financial trends. Venture capitalists have modeled that a fund is successful when one portfolio company scores a massive return in roughly ten years, even if the rest fail, because of Power Law dynamics relating to mechanisms in financial valuation. This reliance on models is expounded by MacKenzie in his book An Engine, Not a Camera. MacKenzie argues that models are creators of reality rather than modeling an external world ‘out there.’ This is why certain business models that fit the currently prevailing VC model are being funded more than other innovative startups.

This ‘go big or go home’ mentality, which encapsulates what I call ‘2nd Wave Venture Capital,’ has changed the way technologies have been made over the last thirty years. It has in some ways commodified startup VC funding, as only specific technologies fit this model. For example, enterprise software-as-a-service (SaaS) subscription software fits this model to a tee; SaaS companies have low costs and can scale exponentially in a financial sense. Direct-to- consumer (DTC) brands have also become a mainstay over the last decade, as they can also quickly and exponentially grow using online advertising and social media. However, many sectors were strong growth is possible that could benefit from the innovative VC model have been neglected. This has started to change, especially after the Covid-19 pandemic. A ‘3rd Wave VC’ is beginning to appear, featuring decentralization, longer-term horizons, and mindful consumption, and sustainability built into analysis. Because of the financial motives behind how startups get funding, and how this in turn determines much of the technical innovation we have today, it is important for HCI to include finance in its purview.

I believe it is necessary to look at technology production in a way that significantly broadens the scope of HCI. Robert Pirsig proposes a philosophical concept of ‘Quality’ in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance; it isn’t one or the other. He argues that Quality lies at the harmonious synthesis of both rational problem-solving skills that are goal-directed and the romantic vision of being in the moment and joy. Being able to include traditionally Romantic ideals in systems currently dominated by Classical thought makes room for a more holistic HCI to exist. Using etymology as tool again, ‘ecology’ literally shares the same root as economics, instead meaning the study of a place or house. Considering the roots of technology, economics, and ecology, it is natural to discuss them under the same umbrella.

Looking at HCI through the lens of Quality, it is easy to include ecology in the conversation. The technology industry often neglects its physical impact on the world; a more ethical HCI should include discard studies and sustainable product design in its scope. I believe it is unethical to aid in the construction of technologies that are laying waste to the planet. This is especially true considering that the most harmful side-effects of digital technology’s physical artifacts today, e-waste and mining related waste, are impacting already disadvantaged communities on the periphery of the tech ecosystem exponentially more than those at the center. Further, many domains of the technology industry continue to neglect its impact on the psyche; a more ethical HCI should be aware of potential harmful impacts, again referencing Noble and Fogg, as well as Némery and Brangier. It is unethical to build technologies that are discriminatory or harmfully addictive, even if made so unintentionally. The technology and VC industries often atomizes laborers, making it more difficult to realize systemic failures; a more ethical HCI should include political economy and finance history in its scope. Returning to the origins of techné, Human-computer interaction should aspire to view software production as an art and skill entrenched in its broader context.

Current systems of technology production are rooted in old and unideal stories of economics and management that still haunt us today. These ideas bound contributing factors to technology’s development. Because of this, I believe a new ethics of human-computer interaction is necessary, a new way to view technology production. The fields of ethics concerns matters of value and morality: this is why I believe ethics is particularly important. My new ethics of HCI features an interdisciplinary scope that includes finance history, ecology, sociology, computer science, and philosophy to paint a more concrete picture of how technologies are made and how they impact society. A new ethics of HCI would result in production that is aware of its context, with the aim of creating products of Quality that please and benefit those who interact with it.

List of Works

Concentration

Bostrom, Nick. Superintelligence. Oxford University Press, 1 May 2016.

Fogg, B.J. “Persuasive Technologies.” Communications of the ACM, vol. 42, no. 5, May 1999.

MacKenzie, Donald. An Engine, Not a Camera: How Financial Models Shape Markets. MIT Press, 29 Aug. 2008.

McLuhan, Marshall, and Lewis Lapham. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. MIT Press, 20 Oct. 1994.

Némery, Alexandra, and Eric Brangier. “Set of Guidelines for Persuasive Interfaces: Organization and Validation of the Criteria.” Journal of Usability Studies, vol. 9, no. 3, May 2014, pp. 105-128, dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/2817713.2817716.

Nicholas, Tom. VC: An American History. Harvard University Press, 9 Jul. 2019.

Pirsig, Robert. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Mariner Books, 1974. [CPC]

Posner, Miriam. “Agile and the Long Crisis of Software.” Logic Magazine, 27 Mar. 2022.ogicmag.io/clouds/agile-and-the-long-crisis-of-software/. [CPC]

Rankin, Joy Lisi. A People’s History of Computing in the United States. Harvard UniversityPress, 8 Oct. 2018.

Zuboff, Shoshana. In The Age Of The Smart Machine: The Future Of Work And Power. Basics Books, 2 Oct. 1989.

Social and/or Natural Sciences

Graeber, David, and David Wengrow. The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. MacMillan Publishers, 2021. [CPC]

Marx, Karl. “Capital: The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret Thereof.” 2nd. Ed., edited by Robert Tucker, W.W. Norton & Company, 1978. [HIS]

Noble, Safiya. Algorithms of Oppression. New York University Press, 2018. [CPC] Ong, Walter. Orality and Literacy. Routledge, 3rd Ed., 2012. [HIS]

Scott, James. Seeing Like a State. Yale University Press, 2020. [CPC]

Weber, Max. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. 1905.

Humanities

Fox, Justin. The Myth of the Rational Market. Harper Business, 2011. [CPC]

Gibbs, Jeff. “Michael Moore Presents: Planet of the Humans.” YouTube, uploaded by Michael Moore, 21 Apr. 2020, youtu.be/Zk11vI-7czE.

Hallnäs, Lars, and Johan Redström. “Slow Technology: Designing for Reflection.” Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 201-212, dx.doi.org/10.1007/PL00000019.

Krippner, Greta. Capitalizing On Crisis: The Political Origins of the Rise of Finance. Harvard University Press, 2012.

McDonough, William, and Michael Braungart, Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. North Point Press, 2002. Wells, H.G. The Time Machine. 1895. [HIS]

Historical (Pre- and Early-Modern)

Laozi, Tao Te Ching. Project Gutenberg, translated by James Legge. gutenberg.org/files/216/216- h/216-h.htm.

Machiavelli, Nicolo. The Prince. Project Gutenberg, translated by W. K. Marriott. gutenberg.org/ files/1232/1232-h/1232-h.htm.

Plato, Phaedrus, translated by Nehemas and Woodruff. [HIS]

Plato, Allegory of the Cave. Martino Fine Publishing, translated by Benjamin Jowett, 2018. Vyasa, The Bhagavad-Gita, translated by Barbara Stoler Miller.

Xenophon, Oeconomicus. ed. and trans. Sarah Pomeroy, 1994. [HIS]

Xenophon, Ways and Means or Revenues (Poroi), translated by Ambler and Shulsky (2018). [HIS]

What are some examples of that "3rd Wave VC" you mentionned